By Welton Jones

San Diego Union-Tribune

Sunday, April 5, 1998

In the spring of 1939, Eldred Peck skipped graduation at UC Berkeley and,

with $160 and a letter of introduction in his pocket, took a chair car to

New York.

Three days later, he stepped off the train in Manhattan as Gregory Peck,

the actor.

Growing up in San Diego, he says now: "I never liked the name Eldred. Since

nobody knew me in New York, I just changed to my middle name."

Within five years, he rode that name back out to California as one of

Hollywood's most promising new stars.

The theater gripped Gregory Peck so firmly in his pre-movie days that he

sought it out again after his film career was established. In 1947, with

fellow rising stars Dorothy McGuire and Mel Ferrer, he founded the La Jolla

Playhouse.

Right in his old hometown.

Late this afternoon at Copley Symphony Hall downtown, San Diego's most

distinguished native actor will be home again to celebrate his 82nd

birthday with a performance of his one-man show "A Grand Evening With

Gregory Peck," presented by the La Jolla Playhouse.

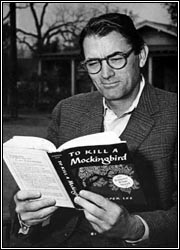

The film career of Gregory Peck is a matter of record. "Twelve O'Clock

High," "Roman Holiday," "The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit," "Moby Dick,"

"Cape Fear," "Arabesque," "To Kill a Mockingbird" . . . the cream of his 55

films are there at the neighborhood video store.

What's far less known, even to Peck's fellow San Diegans, are the origins

of that 28-year-old movie star who debuted in 1944 with "Days of Glory" and

"The Keys of the Kingdom."

Since Peck has spent little of the past 60 years in San Diego, stories of

his youth have accumulated a patina of legend with the accompanying vague

inaccuracies. But there still are people around who remember young Eldred.

At San Diego High School in the early 1930s, he was well-liked, remembers

prominent San Diegan Phil Klauber, a classmate. "Not noisy. Friendly.

Attractive."

"A bit dim," is the way Peck remembers Eldred.

Peck's father, also a Gregory but nicknamed "Doc," was La Jolla's first and

only pharmacist when the boy was born April 5, 1916. That didn't last long,

though. By 1917, the store at 7914 Girard Ave. was Reed's Drug Store and

the Peck family had moved from 7744 Fay Ave. to 3520 Front St. in

Hillcrest. Something about a dishonest bookkeeper.

Doc Peck went to work downtown, at the famed Ferris and Ferris Drug Store

on the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and Market Street, for years the

only 24-hour pharmacy in San Diego County.

Although the family moved back to La Jolla in 1921 (7804 Silverado St.) all

was not well. The next year, the Pecks divorced and 6-year-old Eldred left

town with his mother, the former Bernice (Bunny) Ayres.

Quite soon, the boy was back in La Jolla living with his grandmother, Kate

Ayres (7826 Herschel St. and, later, 4508 Exchange Place), who steered him

through the first five grades at La Jolla Grammar School. Doc drove to La

Jolla for visits each Thursday. And Bunny, who married a traveling

salesman, visited on occasion.

At 10, young Eldred was sent to St. John's Military Academy in Los Angeles.

"I guess," he was saying recently by telephone from his home in L.A.'s

exclusive Holmby Hills, "they decided I was too happy in my grandmother's

bungalow with my bike and my dog."

At St. John's, Peck loved "the military discipline, the uniforms, the

the nuns and the sports." His last year in the grade 1-9 academy,

he was a cadet captain.

In 1930, at age 14, he moved in with his father, at 2205 Broadway, and

entered San Diego High School. Says Peck: "Those were my grandmother's

apartments in Golden Hill. We batched it."

Although it was only 14 blocks to school, Peck took the streetcar,

transferring at Broadway and 12th Avenue.

"What did I do in high school? I grew from 5 feet 4 inches to 6 feet 2

inches. I think I was struggling. It wasn't until my last year there that I

began finding myself. I could get a date. And row a little."

He rowed enough to be accepted at the San Diego Rowing Club, where he

learned about "camaraderie, making an effort, sticking to it, not

quitting." At school, he got into the glee club of Walter (Pop) Reyer --

"If you could hit a few notes, you were in. I tried never to be heard."

And, yes, he did go out for football. His brush with greatness came in

B-team tryouts.

"We had great football teams then. The quarterback was Cotton Warburton,

about 165 pounds, swift, elusive, later a famous star at USC. In a

scrimmage one day, he was coming right at me. I closed my eyes, threw

myself toward him and got hit with his knee as he went by.

"Though stunned, I scrambled to my feet and was proud ever after."

Opting out

Doc Peck, who stayed at Ferris and Ferris until he retired at 65 in 1951,

preferred the night shift, so he and his son didn't see a lot of each

other. But he was clear about his ambition for the boy: He wanted Eldred to

be a doctor.

After graduating from San Diego High in 1933, "I tried for a while," Peck

remembers. "At San Diego State I took mostly science. I had to get some

grades to get into Cal."

By the time he left for Berkeley, Peck was an English major. "Having wisely

opted out of medicine," he says, "I was ready to be a newspaper reporter or

to write reviews or to be a college professor. I felt comfortable with the

idea. I just loved it, in fact."

At Cal, he took up rowing again. And he also discovered a whole new world.

"One of the things I loved about Cal was the eccentrics. The professors who

served turkey hash and red wine with string quartets at home on Sunday

evenings.

"There was `Bull' Durham, an English professor who loved to recite

Shakespeare. He spent a semester getting in shape, then took a sabbatical

and married Judith Anderson. He returned looking just terrible but still

married. Not for long, though.

"There was a philosophy prof named something like Stephen Pepper -- always

called `Dr. Pepper,' of course. And there was Edwin Duerr, persuasive, with

wisps of hair under his tweed hat and thick glasses, the esteemed director

of the little theater."

On campus one day, Duerr approached the towering Peck, who was wearing his

navy-blue sweater with the big white "C" for rowing, and asked him to try

out for a play.

"What play?" asked Peck, whose theatrical experience was limited to a

high-school variety show.

"For `Moby Dick'," replied the professor. "I have a short, fat Ahab and I

need a tall, skinny Starbuck."

A few months later, in love with a dream, Peck would catch that train east.

Amusement zone

"My letter of introduction, from my stepfather in San Francisco, was to

this big man with many interests, way up in a skyscraper on John Street.

`What do you want to do?' he asked after reading the letter. `Be an actor,'

I told him. He thought for a moment. `All I've got is something in the

amusement zone at the (1939) World's Fair.' "

Out at the Fairgrounds in Flushing Meadows, Peck was directed to the owner

of the Meteor Speedway, a thrill ride imported from Belgium that featured,

Peck says, "Caterpillar cars on long arms which climbed the wooden walls as

they went faster with yells and screams."

The boss, a Cockney, looked Peck over and said: "Well, I could make an

opening for a barker. Out front. Twelve hours a day, noon to midnight, a

half-hour on the mike and a half-hour off. Walk around the fair and see

what the other pitchmen do."

The uniform was white coveralls, goggles and flying helmet.

"I started the following Monday," says Peck, "for $25 a week. My job was to

harangue people until they became curious enough to spend 25 cents. `Hey,

young fellow! Got any sporting blood? It's a mile a minute and a thrill a

second!'

"It was the lowest rung of show business. I made friends with the

Pin-Headed Boy From Yucatan. And the Lindy dancers. But I left after six

weeks for a tour-guide job at Rockefeller Center for $40 a week."

And he discovered the Neighborhood Playhouse, a legendary acting school run

by Sanford Meisner. Although he didn't have the tuition money, Peck applied

anyway. The audition was run by the movement teacher, Martha Graham.

"She was pretty fierce, at her prime, a lot of woman. We lined up and ran

around the room for a while. She gave me the green light."

She also gave him, in an exercise class later, the back injury that kept

him out of uniform and in show business during World War II. Studio

biographies used to say the cause was a rowing injury at Cal, but Peck

snorts at this: "In Hollywood, they didn't think a dance class was macho

enough, I guess. I've been trying to straighten out that story for years."

`A happy worker'

At first, Peck waited on tables, and modeled for photographers, appearing

in the Montgomery Ward catalog and, as "a happy worker," for the New Jersey

Power and Light Company.

Rent in his apartment on 54th Street between Fifth and Sixth avenues was $6

a week. He ate at the Automat and the 9-cent breakfast at Nedick's was a

favorite. Ultimately, though, he needed a scholarship. Because he had begun

getting parts.

He spent the summer of 1940 at the Barter Theatre in Virginia, the summers

of 1941 and 1942 in stock companies at Suffern and White Plains in New

York, and on Massachusetts' Cape Cod.

He had done more than 20 shows when he was spotted by the leading Broadway

director Guthrie McClintic, who cast him in a small role for the tour of

George Bernard Shaw's "The Doctor's Dilemma," starring McClintic's famous

wife, Katharine Cornell.

"I got Mr. Danby," says Peck, "with a scene in the third act. And I was

assistant stage manager. I watched that distinguished company at work and I

began to soak up how to do it."

The tour ended in San Francisco, where McClintic rehearsed a new play and

hired Peck to repeat his assistant-stage-manager duties.

"That one did not fare so well," Peck recalls. "We closed in Detroit."

But McClintic knew what he had. He sent Peck out in "Punch and Julia," a

George Batson comedy starring Jane Cowl that flopped out of town. Then, in

September, he presented Peck in his Broadway debut, as a brilliant, young

physician in Emlyn Williams' wartime drama "Morning Star," with Gladys

Cooper and Wendie Barrie. Peck, " ... plays with considerable skill, also

avoiding in his acting the romantic tosh of the writing," wrote Brooks

Atkinson in The New York Times.

The play closed after 24 performances and Peck went right into the next

one, John Patrick's "The Willow and I," with Martha Scott as his leading

lady. That one lasted 28 performances, six more than his third and final

show of the season, Irwin Shaw's drama "Sons and Soldiers," with Max

Reinhardt directing a cast that included Stella Adler and Karl Malden.

Soon Hollywood called. The rest is history.

`Survival of fittest'

Somehow, between "Moby Dick" at Cal in 1938 and "Sons and Soldiers" on

Broadway in 1943, Gregory Peck became one of America's most distinguished

actors.

"My training was telescoped," he said. "I had to pay attention. It was

survival of the fittest."

When he and Ferrer and McGuire founded the La Jolla Playhouse, the idea was

to help Hollywood actors polish their chops.

"We all came from a background of summer theater," he says. "It was

challenging, fun and seemed like the thing to do. And La Jolla seemed the

right place to do it."

The shows were cast and rehearsed in the company's Los Angeles office, then

sent to La Jolla. "We showed up mainly for dress rehearsal and opening

night, playing the role of producers. Then, after the celebration at the

Whaling Bar, I usually had to drive back to be on the set early the next

morning."

Occasionally the founders acted, too. That first summer, Peck and Laraine

Day did so well with "Angel Street" that they toured the show up the coast

and netted $40,000 for the playhouse coffers.

Peck performed in Elliott Nugent's "The Male Animal" during the summer of

1948 and he played the young playwright in Moss Hart's "Light Up the Sky"

during the third summer season in 1949, but then his film schedule became

increasingly demanding.

Although he was active in attempts to revive the playhouse during the

mid-1960s, today will be the first time he's performed for his old theater

in 49 years.

"This will be the 50th time we've done this show since we started it in

Miami -- January 1995. I enjoy it. After the film clips, I'm out there for

an hour and a half, answering questions. I especially like the unexpected

questions. That's a challenge.

"I don't lecture and I don't grind any axes. I just want to entertain."

Copyright 1998 Union-Tribune Publishing Co.

|